To hear the sitar—or as it is sometimes phonetically transliterated in certain regions, the “hitaar“—is to be transported. Its sound is not merely heard; it is felt. It is a cascade of shimmering notes, a resonant drone that seems to vibrate from the very core of the earth, and a melodic voice that can express the entire spectrum of human emotion, from profound devotion to ecstatic joy and deepest sorrow. More than just a musical instrument, the sitar is a vessel of history, a symbol of cultural refinement, and a gateway to the spiritual dimensions of Indian classical music. This article delves into the world of this magnificent instrument, tracing its origins, deconstructits complex anatomy, exploring the philosophy behind its music, and chronicling its momentous journey onto the world stage.

Part 1: The Historical Tapestry – Origins and Evolution

The story of the sitar is woven into the rich and complex cultural fabric of the Indian subcontinent. Its development is not a linear narrative but a fascinating synthesis of indigenous innovation and foreign influence.

The Veena: The Primordial Ancestor

To understand the sitar, one must first look to its ancient predecessor, the veena. The term “veena” in ancient Indian scriptures is a generic name for stringed instruments, but it most famously refers to the Rudra Veena (or Been), a large, fretless, tube-like zither. The Rudra Veena is considered the mother of all Indian stringed instruments. It is an instrument of profound gravity and depth, intimately associated with the practice of Dhrupad, the oldest extant form of Indian classical music. The veena’s design, its long, hollow neck, and the use of gourds for resonance, established the foundational acoustic principles that would later be inherited by the sitar.

The Persian Influence and the Myth of Amir Khusrow

A popular legend, deeply entrenched in cultural lore, credits the 13th-century Sufi mystic, scholar, and musician Amir Khusrow with the invention of the sitar. Khusrow, a towering figure in the courts of the Delhi Sultanate, was a prolific innovator in music and poetry. The story goes that he modified the Persian setar (meaning “three strings”) by combining it with the structural principles of the Indian veena. While this is a compelling narrative that symbolizes the Indo-Persian cultural fusion of the era, most modern scholars consider it apocryphal. The instrument we recognize as the sitar today likely evolved several centuries later.

The Emergence in Mughal India

The sitar truly began to take its modern form in the 18th century, during the later period of the Mughal Empire. As the Mughal court culture flourished in Delhi and Lucknow, there was a cross-pollination between the Persian-Turkic musical traditions of the rulers and the ancient Hindu traditions of the land. Luthiers and musicians experimented with the design of the veena, making it smaller, more portable, and adapting it to the emerging, more florid style of Khayal singing, which was replacing the austere Dhrupad in popularity. It was during this period that the sitar gained its distinctive frets and the sympathetic strings that give it its ethereal, buzzing resonance.

The 20th Century and the Great Gharana System

The 20th century was the golden age for the sitar. The instrument found its ultimate ambassadors in a series of musical geniuses who not only perfected its technique but also systematized its pedagogy. The development of the gharana system—schools of musical thought tied to specific families and geographical regions—was crucial. The two most influential gharanas for the sitar are:

- The Imdadkhani Gharana (Etawah Gharana): Founded by Ustad Imdad Khan, this school is known for the gayaki ang (vocal style), where the sitar is played to mimic the fluidity and nuances of the human voice. Its most famous proponent was Ustad Vilayat Khan, whose style was characterized by its breathtaking beauty and emotional depth.

- The Maihar Gharana: Founded by Ustad Allauddin Khan, this gharana is known for its robust, tantrakari ang (instrumental style), which emphasizes clear, precise note articulation and complex rhythmic play. Its most iconic figure was Pandit Ravi Shankar, who would become the instrument’s global messenger.

It was the rivalry and mutual respect between maestros like Vilayat Khan and Ravi Shankar that pushed the technical and expressive boundaries of the sitar to unprecedented heights.

Part 2: Anatomy of a Sonic Marvel – Deconstructing the Sitar

The sitar’s unique sound is a direct result of its intricate and highly specialized physical structure. Every component, from the choice of wood to the curve of the frets, plays a critical role in shaping its voice.

1. The Tumbas (Gourds)

The most visually striking feature of the sitar is its resonating chambers. A primary, large, pear-shaped gourd (tumba) forms the body of the instrument. Often, a second, smaller gourd is attached at the top of the neck, which rests on the player’s left shoulder. These gourds, traditionally made from dried and hollowed-out calabash squash, are responsible for the sitar’s characteristic rich, resonant, and sustaining tone. The use of a natural, organic material contributes to the warmth and depth of the sound. Modern sitars sometimes use gourds made from synthetic materials for durability, but purists argue that they lack the acoustic complexity of the natural vegetable gourd.

2. The Dandi (Neck)

The long, hollow neck (dandi) is typically crafted from tun wood (Indian cedar) or teak. It is wide and rounded, providing a platform for the raised, movable frets. The hollow nature of the neck acts as an additional resonating chamber, amplifying the sound of the strings.

3. The Tarafdar (Sympathetic Strings)

This is one of the sitar’s defining features. Running underneath the main frets are a set of 11 to 13 thin, metallic strings known as the tarafdar or sympathetic strings. These strings are never plucked directly by the performer. Instead, they are tuned to the notes of the raga being played. When the main strings are plucked, the corresponding sympathetic strings vibrate “in sympathy,” creating a continuous, shimmering halo of sound around the main melody. This is the source of the sitar’s iconic, ethereal drone and its immense sonic presence.

4. The Main Playing Strings

There are typically six or seven main strings running over the curved frets. These include:

- The baj tar (main playing string), used for playing the melody.

- The jhala tar, used for the rhythmic, percussive jhala sections.

- One or two chikari strings, which are constantly tuned to the tonic (Sa) and are repeatedly plucked to provide a rhythmic drone and accentuate the beat.

- One or two laraj strings, which are used for drone effects.

5. The Frets (Pardā)

The frets of a sitar are not fixed into the neck like those of a guitar. They are heavy, curved metal bars (usually brass or silver-plated) that are tied onto the neck with cotton or nylon thread. This allows for their precise positioning and adjustment. The ability to move the frets is essential because the intervals between notes in Indian classical music are not standardized like in Western equal temperament. The exact pitch of a note can vary depending on the raga. A musician must often slightly raise or lower a fret to achieve the precise, subtle intonation (shruti) required for a particular raga.

6. The Mizrāb (Plectrum)

The sitar is played with a wire plectrum (mizrāb) worn on the index finger of the right hand. The use of a hard, metallic plectrum striking against metal strings is what produces the sitar’s bright, penetrating attack. The middle finger is sometimes also fitted with a mizrab for faster, more complex patterns.

Part 3: The Philosophy of Sound – Raga, Tala, and the Art of Alap

To play the sitar is not merely to perform music; it is to engage in a deep, spiritual, and philosophical discipline. The music is governed by two foundational pillars: Raga and Tala.

Raga: The Melodic Universe

A raga is far more than a scale or a mode. It is a meticulously defined melodic framework for improvisation and composition. Each raga is a unique combination of notes, with specific rules governing which notes to use, how to approach them, and which phrases are characteristic. But a raga is also an aesthetic and emotional entity. Each one is associated with a particular time of day, season, and a rasa (mood or sentiment), such as love, heroism, peace, or devotion. The musician’s goal is to faithfully explore and reveal the unique personality and emotional landscape of the raga, bringing it to life for the listener.

Tala: The Cyclical Rhythm

Tala is the system of rhythmic cycles that provides the foundation for the metrical structure of the music. A tala is a repeating cycle of a specific number of beats. The most common is Teental, a cycle of 16 beats. The complexity of tala lies in its internal divisions and the intricate patterns (theka) played by the tabla (the accompanying drum). The interplay between the sitarist’s melodic phrases and the steady, yet complex, pulse of the tala creates a captivating rhythmic dialogue.

The Architecture of a Performance: Alap, Jor, Jhala, and Gat

A traditional sitar performance is a carefully structured journey of increasing tempo and complexity.

- Alap: The performance begins with the alap, the unmetered, meditative, and slow exposition of the raga. Without tabla accompaniment, the musician introduces the notes of the raga one by one, exploring their relationships, their emotional color, and their subtle intonations. The alap is the soul of the performance, a spiritual invocation that establishes the mood and depth of the raga. It is a test of the musician’s creativity, patience, and profound understanding of the raga’s essence.

- Jor: Following the alap, the musician gradually introduces a gentle, rhythmic pulse, still without the tabla. This section, the jor, builds upon the melodic foundation of the alap but adds a sense of forward momentum through a steady, unaccented rhythm.

- Jhala: The jhala is the final section of the unmetered part, characterized by its rapid, rhythmic and exciting interplay between the main playing string and the chikari strings. It creates a thrilling, accelerating crescendo that builds anticipation for the entrance of the tabla.

- Gat: With the entry of the tabla, the composition (gat) begins. This is the fixed, pre-composed melodic theme set to a specific tala. The musician states the gat and then begins to improvise around it, creating increasingly complex variations. The performance culminates in a dazzling display of virtuosity, with the sitar and tabla engaging in a call-and-response dialogue (sawal-jawab, or question-answer), pushing each other to greater rhythmic and melodic heights before arriving at a powerful, synchronized conclusion.

Part 4: The Global Odyssey – The Sitar in the Western World

For centuries, the sitar remained within the confines of the Indian subcontinent, a revered but geographically limited tradition. This changed dramatically in the second half of the 20th century, and the man most responsible for this transformation was Pandit Ravi Shankar.

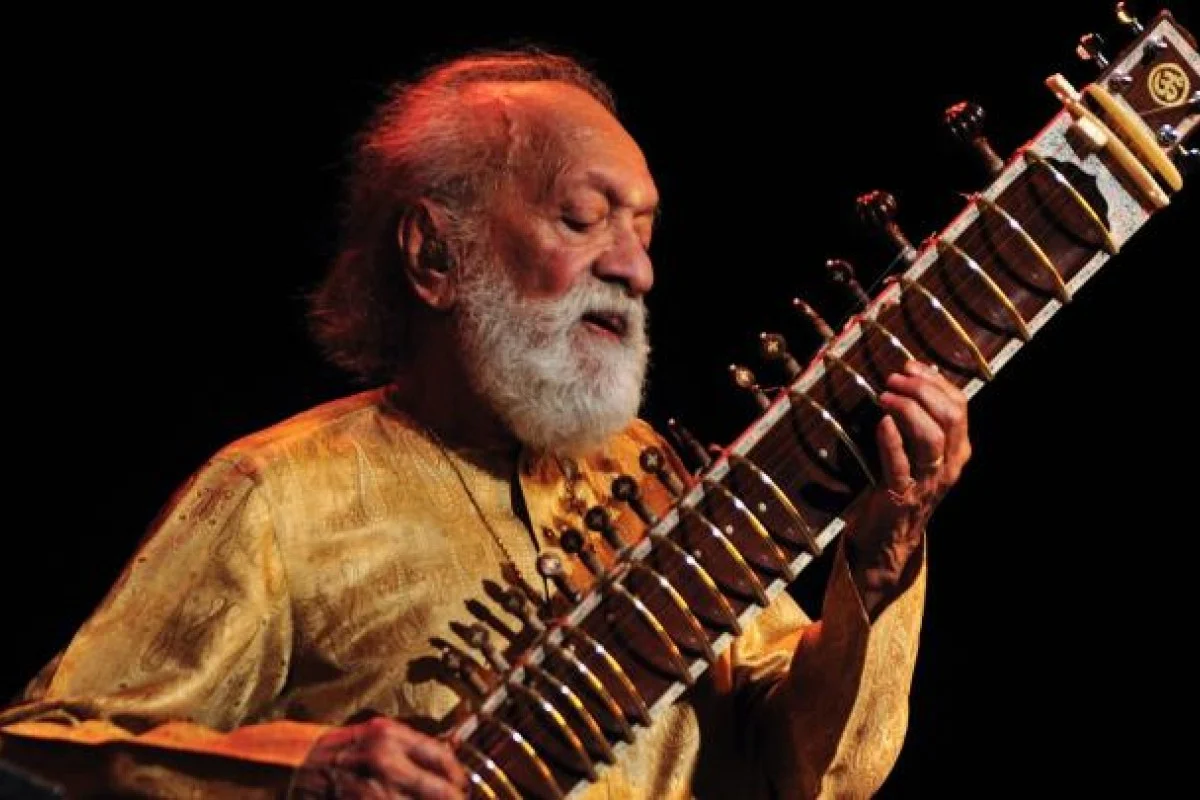

Pandit Ravi Shankar: The Global Messenger

A disciple of Ustad Allauddin Khan and a member of the Maihar Gharana, Ravi Shankar possessed not only sublime musical mastery but also a charismatic stage presence and a deep desire to share his art with the world. His tours of Europe and America in the 1950s and 1960s were a revelation. Western audiences, accustomed to the harmonies and fixed compositions of their own classical tradition, were mesmerized by the sitar’s exotic sound and the hypnotic, improvisatory nature of the music. Shankar was a brilliant communicator, patiently explaining the concepts of raga and tala to his audiences, demystifying the music without diluting its complexity.

The “Beatles” Effect and the Psychedelic Era

The sitar’s journey into global pop culture was catalyzed by a single meeting between Ravi Shankar and George Harrison of The Beatles in 1966. Harrison was profoundly moved by the instrument’s sound and sought out Shankar as his guru. He began to study the sitar and incorporated it into Beatles songs, most notably “Norwegian Wood (This Bird Has Flown).” This single act triggered a massive trend. Almost overnight, the sitar became the sound of the burgeoning hippie counterculture and the psychedelic rock scene. Bands like The Rolling Stones (“Paint It Black”), The Byrds, and others used the sitar to inject an exotic, Eastern, and spiritually “authentic” flavor into their music.

This period was a double-edged sword for Ravi Shankar and traditionalists. While it brought the instrument unprecedented fame, it also led to what Shankar called the “great sitar explosion,” a period of commercial appropriation and often superficial use of the instrument. He was dismayed to see it being played incorrectly as a symbol of drug culture, which stood in stark contrast to the discipline and spirituality he associated with it. Nevertheless, this cultural moment opened a permanent doorway for Indian classical music in the West, inspiring countless Western musicians to explore its depths more seriously.

The Sitar in Contemporary Music

The initial fad faded, but the sitar found a lasting, if niche, place in global music. It has been used evocatively in film scores (notably in Hollywood and Bollywood), in world music fusion projects, and by electronic artists seeking its unique tonal quality. Artists like Anoushka Shankar, Ravi Shankar’s daughter, and Neeladri Kumar, the son of Vijay Kumar, continue to innovate within the tradition while collaborating across genres, ensuring the instrument remains dynamic and relevant.

Part 5: The Living Tradition – Masters and Legacy

The legacy of the sitar is carried forward by a lineage of extraordinary artists. Beyond Ravi Shankar and Vilayat Khan, the 20th century was blessed with other luminaries like Pandit Nikhil Banerjee, whose playing was noted for its purity and profound serenity, and Ustad Shahid Parvez, a modern master of the Imdadkhani Gharana known for his blistering speed and clarity.

Today, the tradition is in robust hands. The aforementioned Anoushka Shankar is a powerful force, both as a torchbearer of her father’s legacy and as a bold composer who addresses contemporary issues like refugee crises and feminism through her music. Virtuosos like Pandit Budhaditya Mukherjee and Shri Partho Sarothy continue to dazzle audiences with their technical mastery and deep musicality.

Conclusion: An Instrument for the Ages

The sitar is more than wood, gourds, and strings. It is a universe of sound, a discipline of the mind and body, and a living, breathing testament to a centuries-old cultural pursuit of the sublime. From the ancient halls where the Rudra Veena echoed with Dhrupad, to the Mughal courts where it acquired its modern form, to the 20th-century concert halls of the world where it found its global voice, the sitar has been a constant companion in the spiritual and artistic journey of a civilization. Its voice—at once melancholic and joyous, meditative and exhilarating—continues to captivate, challenge, and inspire. It is not merely an instrument to be played, but a profound path to be walked, a timeless “hitaar” that still plucks at the strings of the human soul.